Is a museum a hostile concept? How does nationalism affect a museum display?What is the relevance of museums in a digital age? What are the envies and intrigues behind the innocuous-looking displays? And the most sensitive of them all, should you be allowed to touch the objects in a museum? As part my tour of the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastusangrahalaya (CSMVS. Formerly, Prince of Wales Museum) in Mumbai with the In Heritage Project, these were the interesting conversations we covered.

|

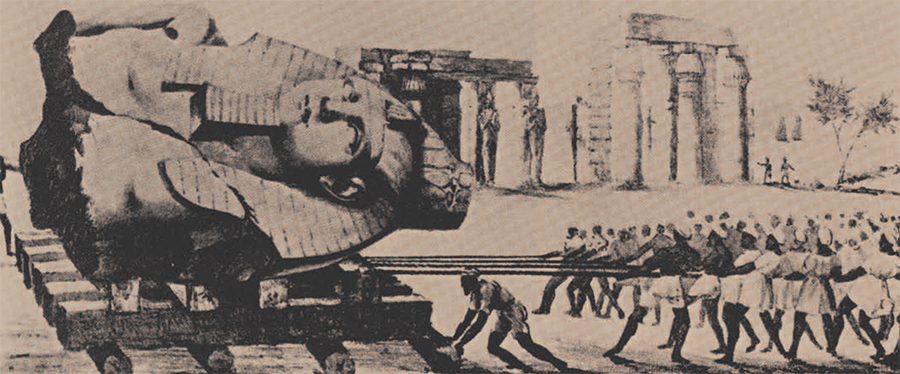

| Belzoni, an early archaeological explorer in Egypt, at work. Source: https://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/the-university-the-museum-and-the-study-of-ancient-egypt/ |

Among the great historical museums of the world, one thing is common, such a impressive collection can never be replicated in the modern day. It's because behind the treasure of knowledge, lies a darker thirst of forbidden treasures. In the 18th and 19th centuries, as Europe made inroads into Asia and Africa, ambitious historical expeditions were sent to these continents to uncover their histories. A prime example is Egypt. When they came across an exciting find, the treasures, including actual parts of monuments were ripped off their sites and shipped to London, Paris and Berlin, and also to a lesser extent, museums in the colonies. Hence why you find so many Egyptian, Babylonian, Assyrian, Indian, or Chinese historical artefacts in these museums. A well stocked museum (or botanical garden) also indicated that a particular country had the political and economic muscle to collect the objects kept within. But then, it is possible that had no one brought these pieces of art into a museum, they would have long since been destroyed.

|

| Assyrian Collection - CSMVS Source:http://scroll.in/article/768431/nineveh-in-bombay-circa-1840s-when-the-splendours-of-ancient-assyria-enraptured-the-city |

| The Lamassu at Vatcha Agiary By Colomen (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons |

How these artefacts landed up at the CSMVS is an interesting story. They were the part of a shipment of 'harvested' treasures heading to the British Museum, which halted at Mumbai. Story goes that the citizenry became very fascinated by the novelty art. When it was finally sent to London, it was a few pieces short. Whether they were gifted or stolen remained a controversy, but the artworks were here to stay, and went on to inspire local architecture too. Just look at the larger than life Lamassu (Assyrian deity with a human head, an ox's body and a bird's wings) that stand guard outside the Vatcha Agiary on D.N. Road!

An even more interesting story is that of the centrepiece painting in the Dorab Tata Gallery. While the museum had it for many years, the artist's signature was never found and it remained anonymous work. In 2006, American Art Historian, Dr. Richard Spear voiced his opinion that the painting might be one by 19th century French artist Antoine Dubost. The museum commenced a long and stringent restoration process, where years of warnish, overpainting and fungus were removed. Finally the artist's signature was revealed - this was indeed Dubost's work, called, 'Sword of Damocles'! But why was the artist's signature hidden?

When Dubost painted 'Sword of Damocles' he displayed it at the Royal Academy where it was acquired by British MP Henry Thomas Hope. Impressed by the artist's work, Hope commissioned him to paint Mrs. Hope and their child. Unfortunately for Dubost, Hope was thoroughly dissatisfied with the results and alleged that someone so bad could not have possibly been responsible for the Damocles painting. Hope enraged Dubost by cutting off a part of the canvas to make it fit in the allotted space in his home. Most importantly, feeling deceived by Dubost, Hope covered over Dubost's signature, and time rendered the work, anonymous.

Read more about the restoration project in this article from Mumbai Mirror.

| Source: http://www.csmvs.in/collection/must-see/51-shiva.html |

It's natural that exhibits like those mentioned above should not be touched, to preserve them for longer, right? Afterall, every museum has a sign that explicitly tells you to not do so. But at the CSMVS, there is an exhibit in the scupture gallery that is in active worship by the staff themselves. The statue of Shiva, dating back stylistically and chronologically to the time when the Elephanta Caves were built. This relic comes from the Baijanath Mahadev Temple in Parel and Alisha told us that it's not uncommon for staff to seek the deity's blessings at the start of the work day.

| The original statue at Parel Source: http://www.vimlapatil.com /vimlablog/parel-shiva-a-great-archeological-discovery/ |

Staying with Parel's contributions to the museum, the same sculpture gallery also holds a replica of a unique statue of Shiva with seven heads. Why a replica - because the local residents refused to give up the original, which is still housed in the bylanes of Parel close to KEM Hospital and is called Baradevi. I asked a few residents of Parel I know, but they appeared unaware of this story, and I do plan to go down and see it for myself. While Alisha's narrative didn't mention it, further reading online led me to an article which explains that the statue was found during road construction work in the 1930s.

A must see in this room are some of the early images of the Buddha made in the Gandhara style. Surprisingly, the image of the Buddha did not emerge in religious art for the initial few centuries. When it did, the images varied visibly in their aesthetic, between the Gandhara style, which reflected Greco-Roman influences, and the Mathura style, which was decidedly Indian. While the images that we currently recognise are results of the eventual prevalence of the latter, the Gandhar style is worth noting since the Buddha's features are inspired by the Greek God Apollo. Apparently this style was preferred by the colonial administration for it hinted at European influences, which they were in a better position to appreciate. But with independence, this hybrid Indo-Greek Buddha appears to have faded from collective memory.

While describing all the exhibits and their stories might not be prudent, I would like to highlight a question that was posed to us by Alisha - how relevant is a museum in the digital age? Most modern museums have detailed photos and descriptions of their exhibits online. It would certainly help in preservation if these delicate objects were not constantly subjected to lights, crowds and pollution. I for one would say that while online cataloguing is a good step to reach a world-wide audience who can't always get to a museum, the physical experience is irreplaceable. I'm certain I'll visit time and again, because you always discover something that you wouldn't have noticed earlier, what about you?

Further Reading:

Disclaimer: I am not a historian, so if there's an error somewhere, do let me know and I'll correct it. Also, I don't own any of the images used in this article. The source is mentioned alongside each image

I have done the heritage walk a couple of years back. Your article is pushing me to now do the museum walk...if I can unchain myself from the digital media.

ReplyDelete